Ceramics and Alchemy

Paper at the conference Between Studio and Factory, Spode factory site, Kingsway, Stoke-on-Trent, 17 & 18 October 2013.

Abstract: On the background of discreet, but still curious coincidences between the origin and interest og alchemists and ceramicists in China as well as in the West, we will try to suggest a certain “art of the fire”, clearly distinct and disconnected with our notions of the Fine Arts. This will be done in examining the parallel humiliations of ceramics and alchemy during the late 18th century, a humiliation which eventually will be revenged by a reading of “Utz”, Bruce Chatwins short novel from 1988. Naturally, due to the limited frame of the talk, we will restrict ourselves to sketch the outlines of this idea.

I.

Warning: imagesx() expects parameter 1 to be resource, boolean given in /home/www/portheim.org/pub/imagecopyresampled.php on line 18

Warning: imagesy() expects parameter 1 to be resource, boolean given in /home/www/portheim.org/pub/imagecopyresampled.php on line 19

Warning: getimagesize(/home/www/barnabooth.portheim.org/museum/mss/piccopassi-1548tp.jpg): failed to open stream: No such file or directory in /home/www/portheim.org/pub/textbild.php on line 63

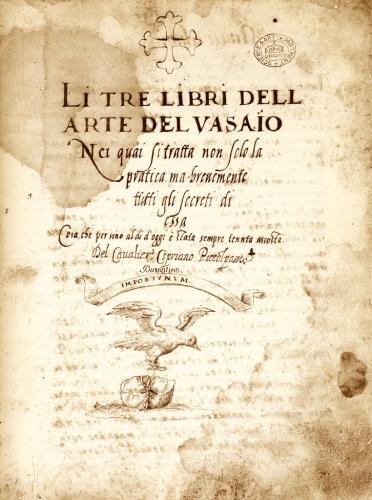

Cipriano Piccolpasso: Li tre libri dell arte del vasaio. 1548. MS. Victoria & Albert Museum

Before arriving for the first time at Spode, I brought a copy of Cipriano Piccolpasso’s The Three Books of the Potter’s Art with me. This is an unique technical manual of ceramics written in 1548, to which art history has never referred. Having no knowledge of, nor any special interest in majolica or the art of the potter, I had nevertheless stumbled across a couple of references to Piccolpasso’s work from an unexpected source, namely the pseudonymous French alchemist Fulcanelli, writing in the early Twentieth Century. For him, The Three Books was not only a tract on ceramics, it was primarily a tract containing, in it’s images, the most profound of alchemical secrets. On of these references read:The Sibyl, questioned on what was a Philosopher, answered: “It is that which can make glass.” Apply you to manufacture it according to our art, without taking account of the processes of glassmaking too much. The industry of the potter would be more instructive to you; see the boards of Piccolpassi, you will find of them one which represents a dove whose legs are attached to a stone. Don’t you have, [...], to seek and find the mastery in a volatile thing? [...] Thus make your mud, then your compound; seal carefully in manner that no spirit can be exhaled; heat the whole according to art until complete calcination. Give the pure portion of the powder obtained in your compound, that you will seal in the same mud.

Fatal error: Cannot redeclare resize() (previously declared in /home/www/portheim.org/pub/imagecopyresampled.php:17) in /home/www/portheim.org/pub/imagecopyresampledpng.php on line 44